2017 Project: Letters from the Land of the Protons

Having managed one post all year in 2016 (albeit a post periodically updated behind its link), I’m going to try to pick up the pace in 2017, with a Dickensian serialization of a set of meditations on a theme.

To introduce the theme, I’ll point you to this recent bit of reporting by Amelia Tate of the New Statesman. Go ahead: click the link and read it. I’ll wait.

OK, you’re back? That was pretty interesting, right? What really caught my attention in Amelia’s story was this sentence:

“Some truly believe in the Mandela Effect, that there has been some glitch in the world, there are parallel universes, or a timeline has been altered and as such little things have got lost.”

But why would people believe a thing like this - that the world doesn’t live by predictable and explicable rules, and that things can just change at random with no explanation? This is the superstitious worldview we left behind with the Enlightenment; how is it possible to hold such a view today, after centuries of proof that the world obeys rational and observable rules? I think Donald Trump, of all people, got it exactly right, when he said a few days ago that “The whole age of computer has made it where nobody knows exactly what’s going on”.

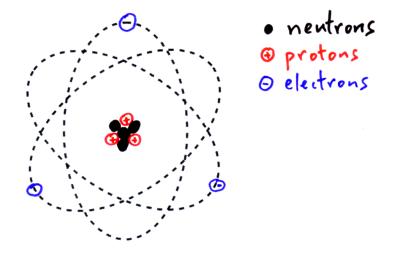

Believing that things in our universe just pop into and out of existence at random intervals is the sort of thing that can only be sustained by people who are not in regular contact with the actual world. And more and more people aren’t in contact with the actual world. They live most of their days in a world of electrons. Electrons are tiny and lightweight, so they can move fast. And they’re tricky. They can be a wave and a particle at the same time. And while you’re not looking they can be in two places at once, as Schrodinger demonstrated. Because electrons can move fast, the world of electrons can change in the blink of an eye. And because they’re tricky, you can never be sure what you’re seeing in the world of electrons isn’t an illusion.

The other world, the pre-computer world, the world of protons, isn’t like that. Protons are big and heavy, and they’re slow and steady. You can just wave your hand and move a bunch of electrons; to move protons you need to use a shovel.

In the world of electrons, a photograph isn’t a record of a real thing; it’s just a painting that looks hyper-real, but can change every time you look away. In the world of protons, a photograph is a chunk of paper or plastic or metal, and it doesn’t change unless you take a knife or a paintbrush to it. In the world of electrons, a news story can say one thing today and another thing tomorrow, and once tomorrow comes it’s difficult or impossible to prove that there has been a change. In the world of protons, a news story is a big sheet of paper with ink on it; it stays on your living room table overnight and when you come back to it tomorrow it’s still there. If you want to get rid of it, you have to set it on fire or get somebody to come to your house and take it away. And if you think somebody has changed it, you can go to your neighbor’s house and see if her copy is the same as yours.

In the world of protons, change is gradual, local, and noticeable. In the world of electrons, change can be rapid, global, and undetectable. Living in the world of electrons, where you’re surrounded all the time by things that change instantly without notice, can make you doubt that things exist and facts are true. It’s not like that in the world of protons; that nail that sticks out of the floorboard keeps pricking your toe until you take care of it. In the world of protons facts are stubborn and things are too.

There’s another difference between the world of protons and the world of electrons: protons are positive, electrically speaking, and the world of protons tends to be a positive place emotionally. That’s not because emotions are electrical (though they are); it’s because things are hard to change in the world of protons, and so humans tend to spend the majority of their time and energy on changes that make their immediate surroundings better.

Electrons are electrically negative, and the world of electrons has turned out to be emotionally negative too. Part of that is selective focus; electrons move so fast that you get them from everywhere all the time - the world of electrons is global. If you’ve got a whole world of news, you can only pay attention to a little bit of it - so you tend to pay attention to the BIGGEST stories, which tend to be spectacular disasters. Protons are slow. Newspapers are much more local than TV networks because moving wads of proton-laden paper around is so slow that a newspaper can’t get very far. Protons make news local, and a local newspaper can’t fill all its pages with stories of spectacular disasters because not that many spectacular disasters happen in any one place at any one time. There’s more room for good news in the slow, local world of protons, because the local bad news is smaller and less dramatic.

Are you with me so far? Maybe you believe me that living in the world of protons will make you happier and show you more truth and fewer lies; maybe you don’t. I’m going to test this theory during 2017. I’m going to spend more time away from my screens in the world of protons, and I’m going to report back.

I’m calling the series Letters from the Land of the Protons, and I’m going to try to write 4 letters a month and post them here. 4 letters a month is kinda like one a week, but with 4 get-out-of-jail-free cards for laziness, flakiness, busyness, and an inability to tell time or remember what day it is.