Similarity Versus Identity

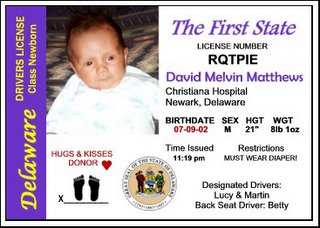

It's a cliche: your driver's license picture doesn't look like you. But if this is really true, then what is the picture for?

It's a cliche: your driver's license picture doesn't look like you. But if this is really true, then what is the picture for?

The stated intent is that the picture is supposed to prevent someone else from using your driver's license. Everyone in the U.S. who's under 21 and enjoying a beer right now knows how effective the picture is for that purpose.

The driver's license picture fails as a descriptive reference because people basically all look the same, and because people don't look very carefully either at pictures or at other people.

Recognition without similarity

Don't believe it? Who's this guy?

![]() You recognize Jesus instantly, even though he didn't actually look like that. In fact, you recognize him no matter what he looks like. He can have brown hair and brown eyes.

You recognize Jesus instantly, even though he didn't actually look like that. In fact, you recognize him no matter what he looks like. He can have brown hair and brown eyes.

He can have black hair and dark eyes.

He can have black hair and dark eyes.

Or he can have blond hair and blue eyes (if you want a really disturbing experience, by the way, go to Google images and search on blond jesus - no quotation marks).

Or he can have blond hair and blue eyes (if you want a really disturbing experience, by the way, go to Google images and search on blond jesus - no quotation marks).

Part of this, of course, is context. If you run across somebody wearing a crown of thorns and sporting a halo, Jesus is going to be on your list of possibles, and you may not look too closely at the height, weight, eye color, hair color, or restrictions fields of his license.

Part of this, of course, is context. If you run across somebody wearing a crown of thorns and sporting a halo, Jesus is going to be on your list of possibles, and you may not look too closely at the height, weight, eye color, hair color, or restrictions fields of his license.

Similarity without recognition

Context is a reasonable guide to recognizing pictures of Jesus, because nobody really knows what he looked like - there aren't any contemporary pictures or descriptions which survive, as far as we know.But even without context, we would all recognize pictures of Jesus, because the Christian community has for centuries been in the habit of using pictures as descriptive references to endow him with certain physical features - tall, thin, long face, beard, benign expression, etc....

Here's another test: do you recognize this guy?

You probably don't, but Jesus would have; when he held up the coin and asked "whose face is on this?", he was looking at this picture - it's Caesar Augustus, and you can bet your last denarius that it's a very good likeness (what do you think happened to sculptors who made Caesar's nose look too big?).

You probably don't, but Jesus would have; when he held up the coin and asked "whose face is on this?", he was looking at this picture - it's Caesar Augustus, and you can bet your last denarius that it's a very good likeness (what do you think happened to sculptors who made Caesar's nose look too big?).

Mistaken Identity

We all have both these problems all the time, even with people we know well. How often have you been at a party, recognized a friend across the room, called out his name, and then realized that the guy across the room is somebody else entirely, and your friend isn't even at the party? That's recognition without similarity.On the other hand, how many times have you answered the phone and conducted a conversation for several minutes before you finally had to break down and ask "I'm sorry, who is this?" (and then had to say "Oh, mom... you sound different - do you have a cold?") That's similarity without recognition.

Cases like this sometimes make the news. Recognition without similarity doesn't have to be based on a picture of your face; a picture of your finger (for example) will do. If you're Brandon Mayfield, a picture of your finger might look something like this:

Somebody who saw a different picture of a fingerprint - maybe the one below - might decide that it looks like a picture of your fingerprint...

Somebody who saw a different picture of a fingerprint - maybe the one below - might decide that it looks like a picture of your fingerprint...

...and if that somebody were the FBI, they might arrest you if the second fingerprint picture was taken at the scene of the Madrid train bombings. You might be more likely to be arrested if the context (for example, the fact that you are a Muslim) reinforced the impression of similarity created by comparing the two fingerprints.

...and if that somebody were the FBI, they might arrest you if the second fingerprint picture was taken at the scene of the Madrid train bombings. You might be more likely to be arrested if the context (for example, the fact that you are a Muslim) reinforced the impression of similarity created by comparing the two fingerprints.

This really happened; these aren't the real fingerprints, but the real second fingerprint was an image of Ouhnane Daoud's finger, and Brandon Mayfield was released.

The point, of course, is that because identity is subjective and identity changes over time, identification is necessarily a process of judging the degree of similarity of two descriptions (or images), and the result of identification is a probability rather than a certainty that the two descriptions refer to the same person or thing.

Art and Ambiguity

The ambiguity of identity creates rich possibilities not only for drama (The Man in The Iron Mask), for comedy (Twelfth Night), and for crime (The Sting), but also for art.My favorite example of art and the ambiguity of identity is the work of J.S.G. Boggs, who creates drawings of banknotes, which he then "spends" by exchanging them for goods and services. He always makes it clear to people that he's giving them artwork, not "real" currency (whatever that means!), but he also always requires change and a receipt.

Several legal cases on several continents have centered around the question "is this a counterfeit banknote, or is it something else?" So far, the answer has always been "it's something else." You can read about Boggs here.